Timmer: The Fed isn't the Market's Only Problem

The strong dollar poses a threat to earnings that hasn't yet been fully appreciated.

Key takeaways

While earnings-growth estimates have been coming down this year, they have remained positive, showing analysts expect growth to continue.

However, these estimates may not yet be fully reflecting the extent of the dollar's rise, which hurts companies that sell their products overseas.

Earnings and Fed policy are key to understanding where the market's fair value might currently lie.

In the markets, life continues to get more surreal by the week. With the Fed relentlessly pursuing an ever-more-restrictive policy, one has to wonder if it will take financial markets to their breaking point, unless the Fed pivots sooner than the markets expect. It all sets up for a very binary set of outcomes—either a recession or no recession.

Earnings remain paramount in understanding how close we may be to tipping into a recession. So far this year, they have consistently showed positive, but slowing, growth. Third-quarter earnings season is about to begin, and estimates are coming down, but only slowly. The estimate progression for 2022 and 2023 continues to indicate a growth slowdown instead of a contraction.

So how good are the earnings estimates? Can analyst and company forecasts be relied upon, or are they perhaps too optimistic?

Earnings estimates may be too high

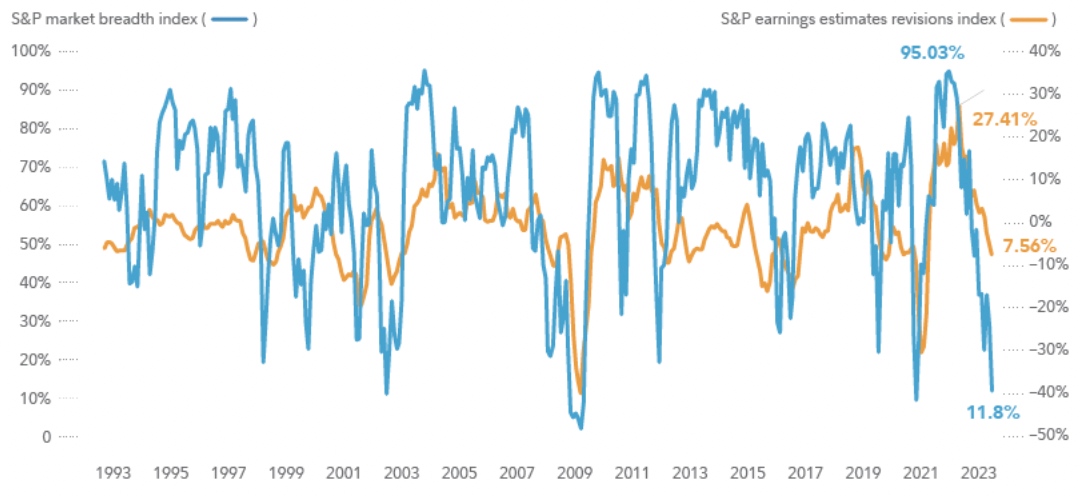

For one thing, there are technical indicators to suggest that earnings estimates ought to be lower than they are, given everything else happening in the markets and economy. For example, below we see the earnings estimates revisions index for the S&P 500®, which shows positive revisions minus negative revisions as a percent of estimates. Compare that to market breadth (the percent of S&P members trading above their own 200-day moving average), and there seems to be a disconnect. In my opinion, earnings revisions should be more negative based on this indicator.

Expected Earnings vs. Market Breadth

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Market breadth represents the percent of S&P 500 index constituents trading above their respective 200-day moving averages. Earnings estimates revisions index represents S&P 500 index constituents experience positive earnings estimate revisions, minus those experiencing negative earnings estimate revisions, expressed as a percentage of index members. Source: First Call, I/B/E/S.

But there is also a key fundamental economic reason why earnings estimates should perhaps be lower than they currently are, and that is the strong dollar.

Around 40% of revenues for S&P 500 companies come from outside the US. When the dollar rises against, say, the euro, as it has done in the last year, then a company's euro-denominated sales are worth less once they're exchanged into dollars.

So the sharply rising dollar should have a noticeable impact on revenues, and by extension, profit margins and earnings. Moreover, the dollar's rate of change tends to lead earnings, with the related change in earnings following some 2–3 quarters after the dollar's change in value.

We see the same disconnect when comparing the dollar's rate of change to the expected earnings-per-share growth rate. Estimates should be coming down faster, it seems.

Expected Earnings vs. the Dollar

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. US dollar index (DXY) measures changes in the dollar’s value relative to a basket of major currencies. Expected earnings-per-share growth rate is measured by comparing expected earnings for the next 12 months with actual earnings over the previous 12 months. Source: First Call, I/B/E/S.

One sees a similar story when looking at expected revenue growth. The consensus estimate is that growth in revenue per share will fall to 4% in 2023, and stay there for 2 years. Unless companies are perfectly hedging their foreign-currency exposures, that estimate seems too high.

Fair value is a quickly moving target

So based on the dollar and market breadth, it seems like we might get a few negative surprises during the upcoming earnings seasons. If, based on the above, earnings for the next 12 months are flat instead of growing by 7% (as currently expected), then the math on the market's fair value changes for the worse.

As I have noted before, price is at the intersection of valuation and earnings. Put another way, the market's current fair value essentially depends on 2 figures: the fair-value price-earnings ratio (which is heavily influenced by Fed policy), and earnings.

How do we get a handle on fair value when the goal posts keep moving? For the S&P 500, is it a 15 P/E ratio on the consensus forward earnings-per-share estimate of $235? Or is it a P/E of 13 on flat earnings of $220 per share? That's the difference between an index level of about 3,500 and 2,900. A moving target indeed.

The Fed is now fully restrictive

Of course, Fed policy has been the key driver in moving that target. The main event last month was the September Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, at which the goal posts were moved once again. The market is now anticipating that the terminal, or ending, rate for this Fed cycle will be 4.42%. The chart below shows the new dot plot (which shows, via dots, each individual FOMC participant's assessment of appropriate future interest rate policy), which has taken a decisively hawkish turn.

Expected Future Interest Rates

Secured overnight financing rate is the interest rate charged for borrowing cash overnight collateralized by Treasury Securities. Source: Bloomberg, FMRCo.

The turn in real rates—meaning, interest rates minus expected inflation—has been stunning, with 5-year real rates rising from negative 2.01% to positive 1.64% in less than a year.

This has put monetary policy in a decisively restrictive stance. Based on estimates of future interest rates and future inflation, the Fed is currently expected to reach peak tightening at a real rate of 2.5%. Add another 1 percentage point from quantitative tightening (the reverse of quantitative easing, with the Fed shrinking its balance sheet), and we get to a 3.5% real rate. That puts this cycle in line with past tightening cycles from the last 40 years, all of which led to recessions. It's a sobering thought.

What does this mean for markets?

All of this has not been lost on the stock market, which not surprisingly hit new lows for this bear market in the last week. However, and this is a significant caveat, it's important to remember that finding the market bottom is not as simple as applying a fair-value P/E ratio to the correct earnings-per-share figure.

Historically, both price and the P/E ratio have usually bottomed out well before earnings do. Looking at market cycles over the past 100 years or so, we find that by the time earnings bottom, the P/E ratio is already up 20%, on average, from the lows. It's a nonlinear exercise, to say the least.

Plus, the Fed could theoretically pivot from its hawkish stance at any time, in which case the fair-value P/E would recover. But will the Fed pivot? I imagine central banks around the world may be wishing for this very outcome.