Immigrants with Temporary Protected Status could be offered a path to U.S. citizenship

Immigrants who have time-limited permission to live and work in the United States under Temporary Protected Status (TPS) could be granted a pathway to citizenship.

Immigrants who have time-limited permission to live and work in the United States under a program known as Temporary Protected Status (TPS) could be granted a pathway to citizenship under legislation proposed by President Joe Biden and congressional Democrats.

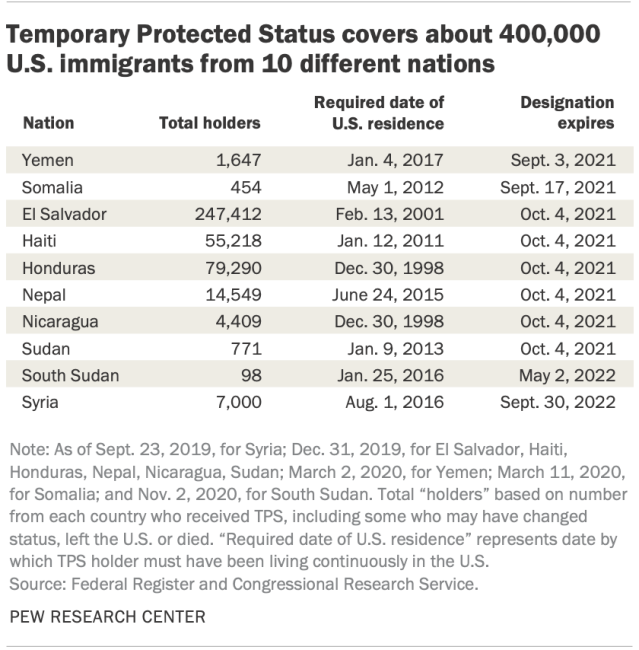

About 400,000 U.S. immigrants from 10 countries currently have TPS, which offers a reprieve from deportation for those who fled designated nations because of war, hurricanes, earthquakes or other extraordinary conditions that could make it dangerous for them to live there. Federal immigration officials may grant TPS status to immigrants for up to 18 months initially based on conditions in their home countries and may repeatedly extend eligibility if dangerous conditions persist.

The Trump administration had sought to end TPS for nearly all beneficiaries, but was blocked from doing so by a series of lawsuits.

Under extensions granted by the Department of Homeland Security in recent years, the earliest that TPS status could expire would be in September for immigrants from Somalia and Yemen. TPS benefits are set to expire in October for those from El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua and Sudan. For TPS beneficiaries from South Sudan and Syria, benefits would expire in 2022. The deadlines for most groups were extended by the Trump administration; the deadline for Syrians was extended by the Biden administration.

After taking office Jan. 20, Biden asked Congress to pass legislation that would allow TPS recipients who meet certain conditions to apply immediately for green cards that let them become lawful permanent residents. TPS currently does not make people automatically eligible for permanent residence or U.S. citizenship.

The legislation proposed by Biden and congressional Democrats would allow TPS holders to apply for citizenship three years after receiving a green card, which is two years earlier than usual for green-card holders. Citizenship would be granted if they pass additional background checks and meet the usual naturalization conditions of knowledge of English and U.S. civics.

The TPS provisions are part of broader proposed legislation that would grant similar benefits to some unauthorized immigrant farmworkers and recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Other U.S. unauthorized immigrants, after applying for temporary legal status, would be required to wait five years to apply for a green card that would make them eligible for citizenship later.

Most TPS beneficiaries have lived in the U.S. for two decades or more. Those from Honduras and Nicaragua were designated eligible based on damage from Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and must have been living in the country since Dec. 30 of that year. The current protections for immigrants from El Salvador applies to those who have lived in the U.S. since Feb. 13, 2001, following a series of earthquakes that killed more than a thousand people and inflicted widespread damage. The TPS designation for Haiti was based on a damaging earthquake in January 2010; immigrants are eligible if they entered the U.S. by early 2011.

Immigrants with TPS live in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, according to the Congressional Research Service. The largest populations live in California, Florida, Texas and New York, which traditionally have had had large immigrant populations.

Once the Department of Homeland Security designates a nation’s immigrants as eligible for Temporary Protected Status, immigrants may apply if they entered the U.S. without authorization or entered on a temporary visa that has expired. Those with a valid temporary visa or another non-immigrant status, such as foreign student, are also eligible to apply.

To be granted TPS, applicants must meet filing deadlines, pay a fee and prove they have lived in the U.S. continuously since the events that triggered relief from deportation. They also must meet criminal record requirements – for example, that they have not been convicted of any felony or two or more misdemeanors while in the U.S., or been engaged in persecuting others or terrorism.

Federal officials are required to announce 60 days before any TPS designation expires whether it will be extended. Without a decision, it automatically extends six months.

Congress and President George H.W. Bush authorized the TPS program in the 1990 immigration law, granting the White House executive power to designate and extend the status to immigrants in the U.S. based on certain criteria.

Deferred Enforced Departure also offers protection from deportation

Another form of temporary relief from deportation, called Deferred Enforced Departure (DED), is imposed at the president’s discretion, rather than as a result of an administrative process in the Department of Homeland Security. It usually follows catastrophes in immigrants’ home countries similar to those that have triggered TPS. Currently, certain immigrants from Liberia and Venezuela are eligible for this benefit and also allowed to apply for authorization to work. Liberian immigrants with DED have relief until June 30, 2022; those from Venezuela have it until July 2022.